Louis Shalako

Claire Laurent had turned in a missing-persons report. Her young man had gone missing, and it just so happened that he not only fit their basic description, but he was also very political, as she put it.

“Joseph was adopted, but he was always my son.” She dabbed a kerchief to her eyes.

“Uh-huh.” Hubert, with his undeniable charm, especially so with the older women, oozed with empathy.

She appeared to be in her early fifties.

“He was never any good in school, and not much of an athlete, although he enjoyed games, as so many boys do.”

Hubert nodded sagely, making small notes as they went along.

“And how did you feel when Joseph became interested in the Parti?”

She shook her head in indeterminate fashion, to her the question was immaterial. Her boy was missing, hadn’t been home for days and that was all she knew.

“You simply must do something.” She was distraught, but still enough in control to be polite, restrained.

It was hard to watch, to see—

He would have to bear that in mind, as well.

She was definitely prosperous, well accessorized with rings, a necklace, earrings, shoes, gloves, the little hat from a slightly-bygone era pinned through her tightly coiffed bun and with a few loose curls dangling out here and there.

It framed an elegant face, powdered and moisturized and still not hiding her real age, which might have been considerable on a second look.

“He was very much a rudderless young man. I mean, at one time. There were a few times when I really did despair. He had tried various things, all of which bored him, or perhaps it was just impossible to get into—I mean, one needs an education for certain things, which was the one thing that was beyond him.” She dabbed at her eyes.

“Was he, ah, a nice guy? I mean, did he have interests?” An open-ended question.

“Oh, yes, absolutely.”

Of course she would say that, and from her perspective, it might even be true. Some kid who read the sports pages, chased girls and still had some sort of political agenda. One had to take it all with a grain of salt.

“So, what about this political stuff? I mean, did he have any friends there, did he mention any names, did he bring anyone home for, ah, lunch or dinner…anything like that? Did he talk about his work.”

“Oh, he certainly had friends. They went off on weekend hikes, that part all seemed very wholesome and healthy. It was good to see him take an interest…” Leather shorts, walking sticks and knee-socks held up with garters.

He could see it in his mind’s eye.

|

| Argh. More bullshit-- |

“So, did your son have any particular, ah, distinguishing marks?” A birthmark, now, that would be priceless—

You couldn’t really say it, but a person could think such things…

“No. Nothing really—” Nothing she could immediately think of.

She might come up with something later, they often did.

On the other side of the one-way mirror, a feature of their row of interview rooms, Levain, Margot and Maintenon stood, watching and listening. All the police could do, was to extend her every courtesy, and on some more human level, hope that perhaps this was not her boy at all, regardless of political affiliations.

Cops were people too.

And again, there was no real way to identify the body…not without wading through another huge pile of bullshit.

Argh.

He growled, deep in his throat, but the room was sound-proofed, after all.

***

The greatest remedy for anger is delay. Seneca. The problem there, was that the killings had not been committed in anger, at least not in the classic sense. No, their perpetrators were pure psychopaths.

He told them that.

|

| Sartre. We sort of expected that... - ed. |

A murder is abstract until you pull the trigger, and after that, you do not understand anything that happens. Sartre.

“The French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre saw all self-deception, no matter how mild, as a form of what he called bad faith; an unwillingness to discover our essence as conscious beings and take true responsibility for ourselves. Ignorance may be bliss, in this view, but it is an irresponsible waste of a life.” So, the gentleman had read a book.

Gilles thought about that, as he sat there.

“How does this concern me.”

The Deuxième Bureau de l'État-major general, that was to say, Military Intelligence, two males in shiny brown trench-coats, sat opposite. Their boss was a certain Colonel Maurice-Henri Gauché, for however long that might last.

He didn’t really care what books they had read, or what justification they had, or thought they had.

The reputation had preceded them. None too particular as to their methods, they were known to use sleep deprivation, starvation, water torture, cigar burns and beatings with rubber hoses in order to obtain not so much confessions as information—information which might be useful, or it might be not, but information never the less. It justified much, in their own eyes.

They were just as happy to dump a person, dead or alive, by the side of the road and charges and formalities be damned.

The one on the left was Bouchard, the one on the right was Leclerc. Bland, clean-shaven, they had left their hats on. They would not be staying long.

“That is one shit-load of wiretaps, er, Gilles. So far, we aren’t getting much of anything at all. We’re only too happy to assist, but we were wondering just how long things might go on.”

He gestured at the pile on his desk.

“We appreciate the copies, would it be possible to send up a machine so we can play them back ourselves…that might take some of the load off of your people.” Shared resources was one thing, but the fact that these boys were somehow involved was distinctly disquieting.

Hubert, had made himself scarce. Margot, talking on the phone, in a low voice and the other hand clamped over an ear, had not been so lucky. As for the others, LeBref, Archambault, one or two more, they were out of the office.

“I need the written transcripts.”

|

| Le Dieuxieme Bureau. These guys aren't even intellectual gangsters. |

“There’s nothing there, Maintenon.” The younger one, even more hard-bitten and pasty-faced than his boss, spoke up. “That, is what we are trying to tell you.”

There was nothing but silence and a long stink in the room—

“What about all these dental records. How in the hell do you expect us to do all of that. What we have here is nothing if not incomplete, considering the long list of names.”

He had the impression that that was that, as the saying went.

“We’ve sent what we could get to Poirier.” The hands were on the knees, and they were preparing to rise.

If that was the best military intelligence had to offer, it was a wonder that they had won the last war, if not the next one—

Another shitty little thought.

“All right, gentlemen, thank you very much.”

***

END

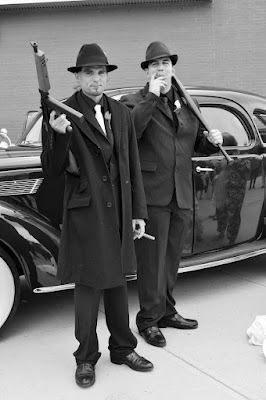

Images. Louis steals them from the internet.

See his books and stories on Amazon.

Louis has art on Fine Art America.

Check out the #superdough food blog.

Thank you for reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please feel free to comment on the blog posts, art or editing.